Program Synthesis in Spreadsheets and CAD

Post Metadata

Program synthesis is a popular topic in programming languages research: the idea of specifying the desired behavior or some part of a program, then having a synthesizer magically fill in the rest of it is very exciting. Many popular program synthesis applications are geared toward traditional programmers: for example, finding fast implementations of bitvector operations for various microarchitectures. But because program synthesis writes the program for the user, there’s no explicit requirement that the user has to know or be interested in programming. In this post, I’ll explore how program synthesis techniques and ideas can help nonprogrammers who don’t have to know that a program even exists – it’s all just “magic”. After some background on program synthesis, I’ll point out the wildly successful program synthesis hidden in Microsoft Excel and a research proposal I’ve been thinking about to help designers specify 3D objects for manufacturing.

What’s synthesis?

Abstraction is everywhere in programming languages research. Computers are complicated and messy beasts, and us humans use abstraction to wrangle computers to do our bidding. Consider this simple Python snippet:

import requests

response = requests.get("https://example.com/api/value")

n = int(response.json()["value"])

x = n * 2

if x % 3 == 0:

print("Bingo!")

We’re used to thinking that programs are instructions that computers can follow, but there’s a lot of detail missing from these instructions. A programmer might keep some of this detail in their head as they write and read this snippet, but I think it’s clear that programmers don’t think about all of these:

- How long do we wait for

example.comto respond? - What happens if the response is malformed?

- How do we check that

x % 3 == 0? - Do we store

nandxas 32-bit integers? 64-bit? Unbounded? - Which values do we store in memory, and which go in registers?

- How does our message get to the

example.comserver? - Where and how do we display “Bingo!”?

- What is the address space of the program?

- What is the clock speed of our CPU?

- How many electrons can be in a transistor before we count a

0as a1?

Abstraction lets us forget about some of these details and focus on what we choose to care about. High-level languages are an abstraction enabled by compilers: a human can write in an abstract and high-level language, and a compiler fills in missing details like register assignments or jump offsets. We’ve devised a high-level system whose meaning doesn’t depend on those details and a trustworthy compiler to put those details back in.

Program synthesis is similar to compilation, but instead of transforming a high-level program into a lower-level one, program synthesis instead takes a program specification – a description of what properties a user wants out of a program – and somehow synthesizes a program that satisfies the user’s specification. This specification is usually a formal mathematical statement (e.g., the mathematical definition of a function that sorts a list), but LLMs with their famously informal interpretations of statements fit the bill for turning specifications into programs – just with far fewer guarantees than other program synthesis tools. In my opinion, the boundary between synthesis and compilation is a little fuzzy – after all, aren’t high-level programs just specifications for the behavior of a low-level one? I think the line between program synthesis and compilation is more in how the user views the input to the tool: whether they think their input has a programmatic structure (compilation) or that it’s more a description of properties (synthesis).

The most famous tools for program synthesis are SAT (short for SATisfiability) and SMT (stands for Satisfiability Modulo Theories) solvers. I won’t get into the weeds on how they work, but they’re essentially fancy equation solvers. There are ways to encode a program specification “a function that sorts a list” into a mathematical equation, and you throw that at a solver. The solver tries its best to find a program that satisfies the equation, just like a more traditional solver can solve “x^2 = 4” with the solution “x := 2”.

Most program synthesis tools are designed to be used by humans that know how to program. This makes sense, as the people that know how to program can most effectively cope with the difficulty of specifying their desired program properties in the format that SAT/SMT solvers want. Additionally, programmers can spot check synthesized output programs, and they can better rationalize and predict the quirks and pitfalls that solvers tend to have. But none of these are hard stops against nonprogrammers using program synthesis – after all, program synthesis should be able to do all the programming for us, if only we can set it up just right.

FlashFill

Microsoft Excel is a ubiquitous spreadsheet editor. In its simplest form, one can use it to arrange text and numbers in a 2D grid. Its expressive power comes from the programming language it has to manipulate values in a spreadsheet: you can write equations that reference existing values in the spreadsheet and calculate new ones. Excel’s language is fully featured, including plenty of operations for manipulating strings and numbers. The Excel pros can use the language to do impressive and useful things, but most Excel users are more casual. We might remember a few Excel operations, but anything beyond the basics is out of our reach. Instead of using Excel’s programming language, we might resort to manually calculating values ourselves and entering them in.

Here’s an example adapted from the original FlashFill paper: we’ve been given some collection of phone numbers from a form, and we’d like to calculate their area codes. We manually type out the first three, but then our knight in shining armor, FlashFill, comes in to save the day: it’s read our mind and calculated the remaining values (italicized) for us. We press tab to accept FlashFill’s gracious help, and go on with our day.

| (907) 284-8421 | 907 |

| (213) 739-3907 | 213 |

| (719) 064-8648 | 719 |

| (480) 917-2734 | 480 |

| (262) 501-9918 | 262 |

| (828) 276-7642 | 828 |

| (916) 733-0309 | 916 |

| (337) 184-4638 | 337 |

| (681) 902-2504 | 681 |

| (970) 448-8197 | 970 |

Of course, FlashFill is not a mind reader. The paper was published in 2011, so it isn’t an LLM either (I have no information on whether the current Excel FlashFill uses AI to make suggestions!). Instead, FlashFill uses program synthesis: given some collection of examples such as the three input-output examples above, it attempts to find formulas in a subset of Excel’s language that meet the “specification” of those input-output examples. This runs behind the scenes, without the user’s knowledge. Although there are many formulas that might match the behavior on those three examples (one could always if-else branch on the inputs), FlashFill somehow pulls out the program that performs our desired area code manipulations. All of this runs in real time as the user is editing the spreadsheet, and the user never even has to realize the system generated a formula – all they do is confirm or deny that the autofilled values are what they wanted.

To keep things running fast, the 2011 paper uses a Version Space Algebra (VSA) to efficiently represent all the programs that the user could want. The VSA makes it easy to specify new examples that constrict program behavior, and to extract programs that are likely to match what users want (i.e., not the degenerate if-else branching). The example I showed above is but a taste of FlashFill’s power – the example from the paper actually normalizes phone numbers to the same syntactic format, handling various spacing, hyphenation, parentheses, and missing area codes. I strongly encourage readers to go play with FlashFill! See if you can devise a string manipulation that it can’t synthesize, or provide some input-output examples that tricks it into synthesizing the “wrong” formula.

FlashFill is a representative of the “Programming by Example” paradigm: a user manually provides a small collection of input-output pairs, and the system synthesizes a function that meets the user’s input-output pairs, and hopefully also does what the user wants on the rest of the data. I believe part of FlashFill’s success was in identifying how well suited the Excel environment is for programming by example:

- Many users don’t care for the intricacies of the Excel language

- Specifying mathematical properties of desired formulas for traditional synthesis would be cumbersome

- The formulas that users want are often short and don’t use many features

- The synthesized formula can be immediately judged by the user on the remaining data points

Many of those above points can be tied back to abstraction: most Excel users choose to view Excel closer to the abstraction layer of just a spreadsheet, rather than a programming language. FlashFill fits very well in this spreadsheet-not-language paradigm: it doesn’t ask the user to change their relationship with Excel. Instead, it deals with the programming language to generate formulas, delivering them up the abstraction chain as actions in the spreadsheet GUI.

CAD

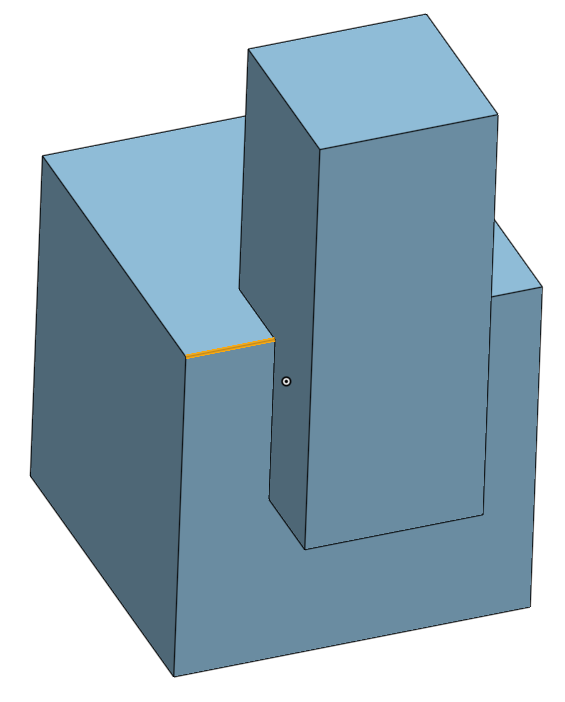

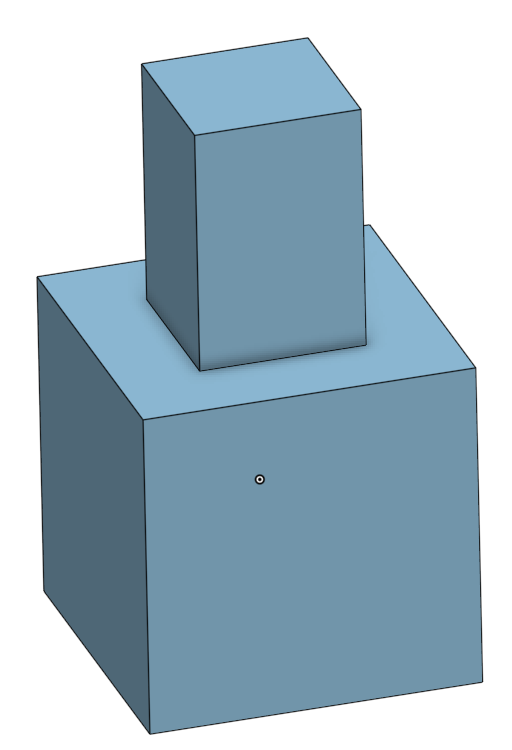

Computer-Aided Design (CAD) is how designers formally specify 2D and 3D objects, often for fabrication or simulation. Mainstream CAD tools are GUI-based; they have users interactively build their models by clicking parts of the model and performing operations. For example, below is one of those operations, called “chamfer”, being executed in Onshape, an online CAD system. A user clicks on some edge to highlight it in gold, and performs the chamfer operation to cut out the material as seen on the right.

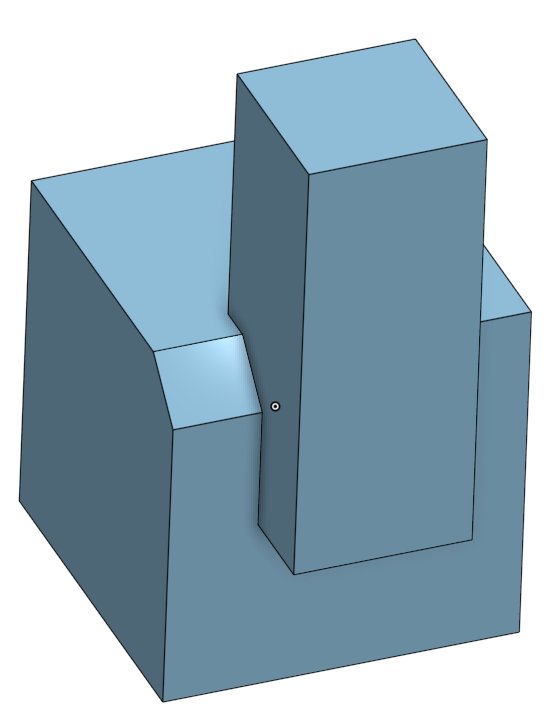

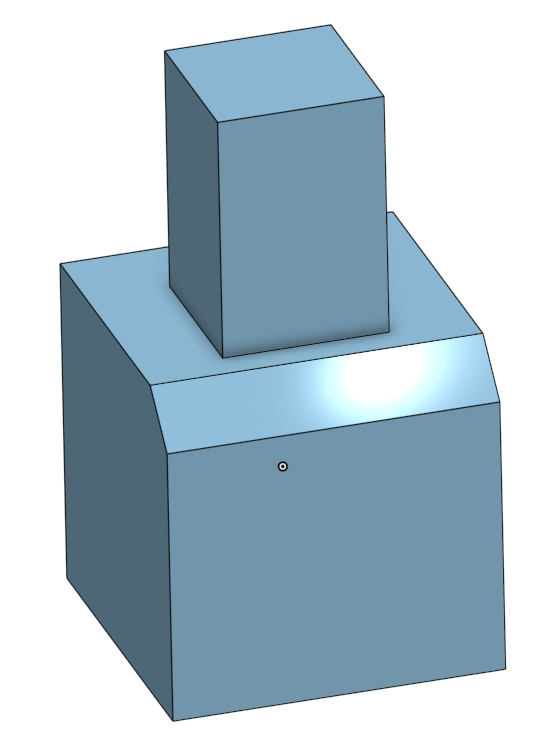

Every time users do this, the CAD system records a reference: some storage of what parts of the model that the user clicked on. It’s quite clear what the user meant to chamfer on the above image, because they clicked it directly. But if the model were edited, the system needs to somehow infer what the user means to chamfer on this slightly new model, and this process is called entity matching. Entity matching can occur when the fundamental operations used to create a CAD model change, or when the numeric parameters change. For example, below is the same model, but with the parameters changed so that the top part is no longer on the side of the bottom cube. The edge that the user clicked on no longer exists in the same form as it did before; now it’s been merged with another edge to form a long one. It’s now up to the system to infer whether the user would like this merged edge to be chamfered or to be left alone – Onshape infers that the user does want the edge chamfered. But note that it’s certainly possible that a user would have wanted the edge to not be chamfered: in this case, they would have to find the bug (easy in our simple case) and correct it manually.

Entity matching is frequently used when exploring a design family: a function from some numeric parameter domain to a family of related models. Examples of design families might be a collection of variously sized and threaded screws, configurations for a 3D printed drone body, or a family of architectural designs for buildings. Parameters often represent dimensions, offsets, or options. Design families might be used for customization, or they might be given to algorithms that optimize an objective function to find the most performant member of the design family. Because entity matching is a heuristic inference, there’s no way that it can be expected to be perfect. Some folks at UW (colleagues of mine!) wrote a paper all about how users encounter and debug entity matching failures, alongside developing a tool to help users find these entity matching problems. They found that it can be quite difficult to correct entity matching’s failures because the visible failure in the model might be caused by entity matching failures that happened much earlier at an unknown point in the model’s creation. When there are hundreds or thousands of operations in a model, or if you didn’t make the model yourself, entity matching failures can be a real thorn in the side.

I believe that viewing entity matching as program synthesis leads to some interesting ideas on how to manage references for users. Current entity matching solutions in mainstream CAD systems attempt to infer user intent from only a single example of which parts of the model the user clicked on – there is a single trusted reference model, and whenever edits are made, entity matching is used to infer intent from that trusted model. But if the user is creating a design family, heuristics can fail to generalize that reference of user-defined behavior across the entire parametric space. This is a problem in expressivity: using entity matching to infer intent from GUI interactions abstracts the burden of references, but users no longer have control over their model’s behavior as it is edited. If heuristics fail to infer user intent, there’s no way for a user to specify their design family correctly.

There are existing alternatives for when users need more control over references. One is to forgo references altogether, and manually mimic referencing operations like chamfering by calculating where edges should be across the design family, but this is time-consuming and error-prone. A more scalable solution is to use a query language such as CadQuery: users write queries over models that select exactly the parts that they’d like to chamfer. These queries are often quite short and simple: “select the topmost edge(s)”, or “select the point(s) that were created when transforming this cube”. As long as a query language is sufficiently expressive, queries offer complete control for specifying intent, but they are still not easy to use. CAD is inherently a design-oriented process, so it’s a tall order to ask a user to specify their desired behavior over a model upfront as they design it. There’s also no guarantee that users won’t make errors as they write queries, or whether users will prefer to write queries over their familiar click-and-debug workflow – the ideal CAD abstraction level is just modeling, without any manual query management.

You now might be able to predict where I’m headed with this blog post. Can program synthesis offer some of the expressivity of queries while not disrupting the abstraction that CAD users appreciate? I believe that there are many similarities to Excel’s FlashFill: we don’t want to require users to read or write programs, the synthesized programs are simple with a limited syntax, synthesis must run in real time, and behavior is specified through a small sequence of example input-output pairs. In CAD, those input-output pairs are generated from GUI interactions, where the input is a model and the output is some selection on that model.

However, there are plenty of complications: in FlashFill, the formula plucked from the VSA to recommend to the user is the one that matches certain heuristics. What metrics on CAD reference queries make them more or less likely to agree with a user’s intent? FlashFill additionally benefits from being able to show the user its synthesized formula’s output on the remaining inputs, whereas in design families, continuous parameters or combinatorial explosion make showing all outputs impossible or infeasible. How can we help users verify that synthesized queries are correct without their knowledge of a query language? I’ll admit that I’m still figuring these questions out, and I don’t think there are any definitive answers out there.

In summary, abstraction is a powerful tool in programming languages, and synthesis via programming by example is a way to abstract out even programming itself. I hope that these examples got you to think about where program synthesis can fit into places where programming might not be obviously present.