Exploring Level Editors with Video Souls

Post Metadata

I love level editors, and try to include them in most of my games. They make level design way easier for developers and allow players to add brand new content to a game. We wrote Orblorgo Command with a level editor, and more recently designed a fancy level editor for our new game called Video Souls. Check out the trailer for Video Souls! While on the surface level editors seem like just a simple way to put assets into a game’s world, they can be so much more.

Here are some of my favorite examples:

- Super Mario Maker, a platforming game consisting almost entirely of community-made levels. It is popular and comes with a slick tile-based editor.

- Starcraft’s StarEdit, which allowed players to create entirely new games within the Starcraft engine. Many entire new genres of games were born as custom Starcraft maps and mods.

- Just recently, the game Rhythm Doctor showed off an amazing trailer, with the entire trailer being a single level created in the game’s level editor.

Programming Languages Perspective

From a programming languages perspective, a level editor is a structured editor for an underlying domain-specific programming language (DSL). The editor and the DSL are designed to work together. The level editor provides an interactive view of the underlying language, giving the user tools to manipulate the program in a convenient way.

In the case of Super Mario Maker, the underlying language is a tile-based representation of a 2D platformer level. The syntax of the language is the grid of tiles, each one representing a type of terrain, obstacle, or enemy. The semantics of the language are the rules of the platformer game, the way it behaves over time given the player’s input each frame. In Mario Maker, the blocks define the initial conditions of the level. This makes predicting what will happen difficult, but that’s part of the fun of designing and playing Mario levels!

Challenges

When designing a level editor, I keep in mind a few key challenges:

- Safety: The level editor should prevent players from crashing the game, accessing data they shouldn’t, or eating up too many resources (time or memory).

- Expressivity: The level editor should allow players to create interesting and varied levels. This is often at odds with safety.

- Usability: Level editors are often used by enthusiastic players with little to no programming experience. The level editor must be easy to use and understand.

We’ll see these come up in the context of Video Souls.

Video Souls

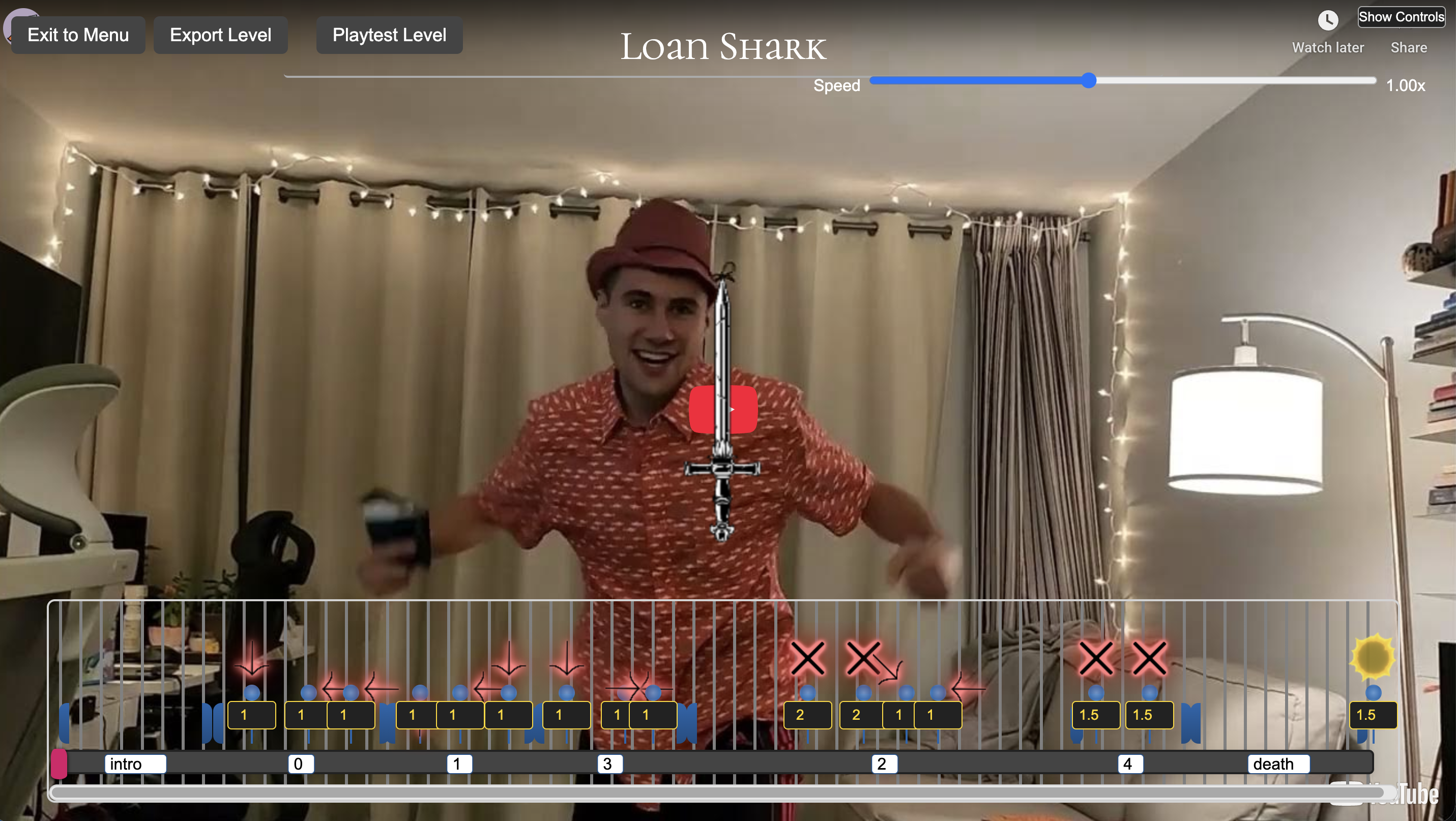

Video Souls is a game that runs directly on YouTube videos in the browser. The player is tasked with defeating enemies shown in the augmented YouTube videos by blocking attacks and counterattacking at the right time. It includes a community level editor that allows players to create their own levels using YouTube videos of their choice.

Here’s how Video Souls balances safety, expressivity, and usability in its level editor.

Expressivity

Video Souls defines a DSL with two parts. The first is a level description language, which describes the timing of enemy attacks and other events in the video. While it has a JSON format, it’s intended to be edited through the level editor UI, which provides a structured view of the level data.

Advanced users can leverage the second part of the Video Souls DSL: custom schedules. Schedules define what attacks enemies use and when, allowing for dynamic and reactive enemy behavior. For example, some enemies might use scary attack after losing over half their health. This is implemented by skipping to different locations in the video, called attack intervals, which can be added in the structured level editor.

Custom schedules are implemented in a subset of vanilla JavaScript as a function called each frame. The function returns a data structure telling the game if it should continue to a different attack interval. This mechanism is expressive because since players can implement complex behaviors using the full power of JavaScript, including storing state in variables outside the function scope.

Here’s a trimmed down example from the repository’s schedule for the “Loan Shark” level. It tracks whether a boss has opened with its basic attack and whether it has fired a special move yet:

var didStartAttack = false;

var didSpecialAttack = false;

return function(state) {

if (!didStartAttack) {

didStartAttack = true;

return { continueNormal: false, transitionToInterval: "0", intervalOffset: 0 };

}

if (state.healthPercentage < 0.6 && !didSpecialAttack) {

didSpecialAttack = true;

return { continueNormal: false, transitionToInterval: "2", intervalOffset: 0 };

}

// Afterward, fall back to random intervals that keep the fight lively

return { continueNormal: true };

};

The closure survives across frames, mutating the didStartAttack and didSpecialAttack variables to keep track of what has happened so far in the fight.

For the level schedules in use currently, see the Video Souls repository’s level schedule examples. I admit that writing level schedules is not super easy, since the function is called each frame and must manage its own state like a low-level state machine. I bet programming languages techniques can help! For example, a better-designed DSL could use delimited continuations to make the schedule more natural to write.1 Continuations would allow the schedule to keep local variables and yield control back to the game engine, receiving more information when control is returned.

Safety

There are two general techniques I use to keep levels safe in Video Souls: restricting the expressivity of the DSL and dynamic sandboxing.

The first technique is applied to the level description language. Level descriptions are limited to a finite set of constructs such as attacks, critical hit opportunities, and intervals. It’s certainly not turing complete, lacking any sort of loop construct.

In order to keep the schedule language safe, we sandbox and timebox the schedule code using a JavaScript interpreter written in JavaScript called JS-Interpreter by Neil Fraser. Thanks, Neil! I think the sandboxed interpreter route is a great solution for any game that wants to allow expressive level scripting.

Both of these techniques limit what players can do by implementing a trusted interpreter. One is for the more limited level description language, and one is for a subset of JavaScript code. It I wasn’t trying to leverage the existing knowledge of JavaScript people have, I might have unified the level description language and schedule language into a single language. As an aside, I’ve heard that it’s possible to safely execute real javascript in a sandboxed iframe, but I’m not clear on how safe this is.

Usability

The biggest way to make a level editor usable is to leverage knowledge users already have. Video Souls levels are probably edited by people who are familiar with YouTube, and possibly video editing. To make the editor usable, I designed it to look and feel similar to video editing software.

At the same time, users are familiar with how to play the game. Leveraging this knowledge, the video editor is designed so that creating a level is the same as playing the level. If users play back the video and block attacks with perfect timing, they’ll map out the level in one try. A video speed slider makes this process more forgiving.

Conclusion

There is so much more to explore here. While in this blog post we applied some ideas from programming languages to level editors, it may also benefit us to apply level editor ideas to programming languages. Structured editors don’t seem to have caught on, despite their incredible potential to make programming more accessible and less error-prone. It could be that a change in perspective could help bridge the gap. For example, it’s possible that defining a range of intermidates between a text editor and a structured editor could help ease the transition. In Video Souls, it would be nice if you could edit the json and see that reflected in the level editor, and vice versa. I’ve seen some of these ideas explored at Ink and Switch, but there’s a lot more to do!

1 Algebraic effects, coroutines, and generators are all related to delimited continuations but are different in subtle ways. I’m not going to try to explain here.↩